Staging:MainPageOld

!!!FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY!!! Please go back. This page is an archive of past thoughts, etc. a working sketchpad/test balloon for brainstorming ideas. What is here is incomplete, possibly inaccurate, and does not represent fully thought-out beliefs of the authors. Thank you for your understanding. An archived copy of the working Main page that has since been replaced.

Welcome!

Welcome Readers! Thank you for taking the time to visit.

If you, like I, have been trying to make sense of this seemingly crazy and ever more complicated world, this site is for you.

The main focus of this site is to use a multidisciplinary approach to attempt to analyze complex, contemporary issues from an objective, and pragmatic perspective. While there are many definitions, this is what I think of as Critical Thinking. And while at first blush that approach may not seem particularly unique, it seems surprisingly rare these days. Analysis often leans toward editorial advocacy; similar to a listening only to the prosecution or the defense in a court case or listening only to one side of a debate. One side is presented in the strongest possible way, and the other side is trivialized and represented weakly. What passes for political debate is often two extremes yelling at each other. A lot of talking, and very little listening. Objectivity is a word that has somehow gone out of favor.

And ideally my goal is to do this all with a sense of humor, respect, and acceptance. This site is very much a work in progress, so I welcome thoughts, suggestions and constructive criticism.

The Most Important Step Forward in Critical Thinking is a Step Back for a Broader Perspective

Almost everything we do requires forward focus. It is essential for our survival and for all problem solving. As humans, we are optimized to be forward oriented. Our eyes only point forward. Our bodies are tuned to moving forward quickly. We can walk/run forward quickly, even over uneven paths, and carry on a conversation at the same time, without much conscious effort. Walking backward on the other hand is slow and takes concentration and conscious effort. Our world and language also reflect this forward-orientation. There are no Track and Field events for running backwards. In swimming races, even the backstroke moves forward. "Forward" is associated with positivity as in "forward-thinking." "Backward" is associated with negativity. And once we are moving forward, momentum allows us to continue moving forward more efficiently, expending less energy.

Our thinking processes work similarly. Once we believe something to be true, we tend to notice evidence that supports our forward momentum, and to discount evidence that challenges it. There is good reason for this. We don't have unlimited time, so optimizing "forward" helps us find reasonable solutions quickly, expends less mental energy, and allows us to move on to the next problem. But while always moving forward is efficient, and usually results in "good-enough" solutions quickly, it doesn't always result in the best solution. Forward focus is tuned to what we see, but not to what we don't see. For example, if we are walking down a path, there may be a shortcut a few steps behind us, but we won't see it if we don't take a step back, or turn around, from time to time. Forward focus may get to our destination quickly, but we may miss an alternate path or an amazing vista. And our momentum can even make us miss alternative paths right in front of us.

A fundamental, but often overlooked, step in critical thinking and problem solving is to fully understand the problem before jumping to solutions. And fully understanding a problem typically requires a step back. Stepping back allows us to better see the big picture, to see other issues that affect our solution, to see a problem from multiple perspectives. It allows us to consider not only what is in plain sight, but what is hidden from view. Even skewed perspectives can give us insights into how others may see a problem. And when dealing with societal problems, it isn't enough to uncover truth, we also need to understand how others will perceive it.

When we step back, we think more about the "why." We look for the cause, not just the symptom. We introduce a healthy skepticism to look at problems from multiple perspectives, we challenge our assumptions, and we see evidence and our opinions more objectively. We can also better take into account how problems and solutions may change with time. The most "logical" solution doesn't always work in practice, nor does a good solution always remain a good solution over time. This is especially important when dealing with issues that involve human behavior.

This isn't meant to minimize the importance of forward-thinking. We will never reach our destination if we only move backward. The main point here is that forward thinking comes naturally, but taking a step back takes more conscious effort. And stepping back is essential for critical thinking.

Stepping Back: Conscious and Subconscious Thought

Most complex real-world problems involve human behavior. The most effective vaccine in the world is not effective if it is not available, or people choose not to take it. And that is what makes complex problems so complex: they involve many variables, some outside our control.

So, I believe that when one steps back, one of the most important aspects of critical thinking is a better understanding of innate human thinking processes. While we recognize that no two humans think exactly alike, and we have free will, it is also important to recognize that all humans share biological traits that have been tuned through evolution. This applies not only to physical characteristics (e.g how our knees bend in one direction) but also to our mental characteristics, the way we think. While this may seem obvious, it is amazing to me how often we overlook this simple fact. And ironically, one of the reasons we overlook it, is that we are biologically predisposed to do just that! Simply put: There is an evolutionary advantage to us ALL being overconfident in our own knowledge and capabilities... and also to deny that we do so. Humans are capable of overriding that tendency on occasion, but we can't all do it all the time, and we can't do it for everything. And that leads to another irony: a key aspect of critical thinking is accepting that we are not humanly capable of always thinking critically and objectively. This applies to even the most adept and experienced critical thinkers. And it helps explain why what we think of as "common sense" is not always shared by others. In short, what seems to us like common sense is sometimes neither common nor sensical.

For me, an epiphany occurred when I stepped back and began to think of our brains as two distinct entities: the conscious and subconscious. Although these entities work together and collaborate, they operate under very different processes and priorities. When we commonly talk about how humans think, we typically are focusing on the conscious brain, even though the subconscious brain accounts for the majority of our thinking processes. The conscious brain is capable of the most complex thinking, and really distinguishes humans from other species, but conscious thought is limited to one thing at a time and is very slow and inefficient compared to the subconscious. Because conscious thought is limited, it must be conserved and used judiciously.

Our subconscious brains are amazing workhorses, with an almost unlimited capacity to be able to make very quick decisions based on limited information. It is absolutely incredible that we share the same brain capabilities of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, and yet are able to cope in this very different modern world. This is predominately due to the adaptability and capacity of our subconscious brains. Our conscious brains are still only capable of handling one problem at a time and aren't even capable of memorizing anything. Isn't it amazing, that our incredibly powerful conscious brains cannot force our subconscious to memorize a name, but rather can only try to influence and coerce? This is why I think it is helpful to think of them as separate entities, working together as a team, but each with "a mind of their own".

Our subconscious is tuned to speed and efficiency. Quickly making "good enough" decisions based on incomplete information and moving on. Doing so means simplifying complex problems full of uncertainty into simpler problems with clear binary answers. (I.e. easy yes/no, true/false choices).

Although these decisions are sometimes wrong and lead us into trouble, I believe it is important to not see these as flaws or cognitive biases, but rather the inevitable consequence of our evolutionary biology and our complex world. I believe that a key foundation for pragmatic critical thinking is simply understanding and accepting this basic fact in ourselves, and in others. Complex problems take on a whole new dimension when we step back and view them from this perspective. As such, much of the writing here will focus on better understanding human thinking processes.

Balance and Tension

One of the most amazing aspects of the human body is our ability to stand upright, to walk, to run, to jump. To maintain our balance without falling down. With all of the advances in technology, engineers are still not able to create a robot that can walk as naturally as a human, much less run and jump. But an important, and often overlooked aspects of balance, is the need for tension. To move, our muscles contract to bend a joint, but another must exist to pull in the opposite direction to straighten it out again. Trees grow upward, their trunks keep them from collapsing, and gravity keeps them from floating away. A delicate balance maintained by "competing" forces.

Our physical world is full of examples how tension can build the strongest structures. For example, a suspension bridge works by the weight of the deck pulling down each side of the cable, keeping the cable in constant tension. The vertical supports hold the cables up in the middle. There is a constant tension between compression and stretching. A suspension bridge is much stronger than a bridge where all the weight is downward on the support structures.

It shouldn't be a surprise that our social and democratic political systems are characterized by political parties pulling in a specific direction. The opposition party is important to maintain balance. Humans are what sociologists call "prosocial." There is a constant push and pull between doing what is best for us personally, and engaging in behaviors that benefit others or society as a whole. Likewise, our subconscious can pull us in one direction, and our conscious is there to provide balance.

Walking a tightrope is a classic analogy for the delicate balance. However, in most real-world cases, there is considerably more room for error before falling off. A better analogy is walking on a sidewalk suspended high in the air. There is significant room for error before one falls off. One can get dangerously close to the edge, but if one doesn't fall, the end result is the same as if one walked safely in the middle.

Another illustration of the importance of tension is to think of a tug-of-war between two teams of athletes. Each is pulling at maximum strength. If one side is stronger than the other, the rope moves slowly in one direction. But if one side suddenly dropped the rope, the other side would fall down, not continue to pull the rope. I.e. each side is dependent on the other providing tension.

It is interesting to note, that In most contexts, the word balance has a positive connotation, but the word tension has negative connotations. This is fascinating because tension is necessary to maintain balance.

Words Matter... Sort of... Sometimes

Most of us would agree that words do matter.

But in most human languages, and certainly in the English language, words have different meanings. Even dictionary definitions are not able to capture the subtle differences that each individual thinks of as the definition, much less the context. The words "I'll kill you" have very different meaning when uttered by good friends, vs. a stranger in a dark alley. And words like "Capitalism" and "Socialism" can be perceived very differently based on a person's political point of view and context. This is exacerbated by our human tendency to simplify complex problems/concepts into much simpler binary choices. For example, many would see Capitalism and Socialism as opposites, but in reality, most Western social and economic systems have some components of each. This is another example of tension/balance in the real world. It is also an example of the need for binary simplification and efficiency. In many cases, treating these concepts as opposites can work well for the point at hand, we'd go crazy if we had to precisely define each word and meaning in every context. But forgetting that it isn't always black and white, that there is almost always a circumstance where there is exception to any rule, can upset the balance.

Complexity is often introduced when two people use different definitions of words and phrases. One can utter a phrase with a specific intent, but the listener may perceive a different meaning and intent. I find that often if you step back and listen carefully, you'll find that many arguments are because the two sides are using different definitions of the same word. The argument is essentially about the definition, yet neither side typically clearly lays out the definition they are using.

One of the phrases we learn early is "Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me." This helps us cope with differing definitions, with emotions, and helps us develop a thick skin and not be overly sensitive. On the other hand, it totally ignores the reality that in many circumstances, words can do great damage, much greater than sticks or stones. Wounds heal and can be forgotten, but words can hurt forever. The sayer may not mean to hurt, they may have uttered it in the heat of emotion, but to the listener, a slight may wound deeply. As children, playing with our friends, few of us would ever forget being singled out with a racial/ethnic slur aimed at us. It hurts and even if healed, leaves a scar.

These are all examples of tension and balance.

A Model for Critical Thinking

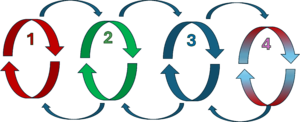

Primary Thinking Loops

The thinking and learning process can be thought of as a "feedback loop." We take in inputs, (e.g. observation, knowledge, sources) we take action, and we observe the result. And that result becomes an input for the next try. This allows us to quicky improve, because we are learning from experience. In most everyday situations, when we reach a "good-enough" solution, we typically move on to another problem. There are 3 main loops in everyday thinking, each involving a step back, each taking more conscious effort.

- Thinking Loop 1: Our most innate/instinctual loop sees the world through a self-oriented, local, and immediate perspective. We try something and we see how it affects us, we see it from our eyes. We don't think of others. Crying babies may associate crying with receiving food or getting their diapers changed, they aren't thinking of the parent who has to feed/change them, or where the food comes from. This is a basic survival instinct. Without that self-focus, the human race would not have thrived as it does.

- Thinking Loop 2: As we grow, we can take a small step back, and we learn to see things from another's perspective. This is also an innate instinct that occurs at about age 4. Cognitive psychologists call this "Theory of Mind." We begin to be able to put ourselves in another's shoes and can imagine what we would do if we were in their shoes. We can see how our actions affect others and the future. Our focus expands from self to family and a wider community.

- Thinking Loop 3: As we grow into adolescence and adulthood we learn to take another step back. We hone our problem-solving ability and can take into account more perspectives. We use reason to apply knowledge from one space into another. Scientists call this "abstraction." Our geographic knowledge expands and we become part of a wider community. Most of our schooling focuses on this third loop. The third loop is the foundation of critical thinking.

The Critical Fourth Loop

Sometimes third loop thinking isn't enough, especially when we are dealing with intractable problems, or other situations that involve human behavior and uncertainty. In the fourth loop, we step back further, we turn around, we consider not only what we see, but also what we don't see.

Complex problems like these can look different when we take another step back into the fourth loop, when we take a break from solution-finding, and focus on problem-understanding. Using the theater analogy, in the fourth loop we take a big step back from the balcony. [Loop 4: The world's a stage] We leave the theater entirely and see it from the outside. We see all those people that are not in the theater at all. Some who might love to see the play, some who don't give a whit about poor Yorick, some stuck in traffic, and some who don't even know the play is going on. All are focused on their own thinking loops, they have things that are higher priority to them than being in the theater at that moment. Added insights come from comparing what you perceive from that viewpoint to what you would perceive from the balcony.

This fourth loop is more difficult, requires significantly more time and effort to step back. It can be quite nebulous and overwhelming. It seldom yields definitive solutions and often uncovers more questions than answers. And it is easy to avoid simply by keeping our forward focus. Stepping back takes significant cognitive effort, time, and a willingness to reexamine our own beliefs. The more that we have been on the current path, the more invested we are, the harder it is to step back.

Innovation and "out-of-the-box" thinking happen in the fourth loop.

A bonus is that when we take time to wallow in the fourth loop, we may discover new insights and perspectives that may not even be directly relevant to the problem at hand, but may provide inspiration and identify useful tools for addressing other problems.

A View From the Fourth Loop

The Subconscious and Conscious Human Brain

Time management is an important, and often overlooked aspect of human thinking. Speed in decision-making is often more important than accuracy. And our brains are evolutionarily wired to make fast decisions. This has become even more important in the modern world, where it is estimated that each human must make over xxx,000 decisions each and every day!

To make fast decisions, evolution has equipped us with a subconscious thinking system that allows us to simplify problems and make quick choices, without requiring conscious thought. And unlike most other species, we also have a conscious thinking system that allows us to handle even more complex problems, albeit at a much slower pace. And more importantly, it can teach, correct, and/or reinforce our subconscious. (Cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls these System 1 and System 2 thinking, aka fast and slow thinking.)

In a nutshell, the role of our subconscious is focused on efficiency, making "good-enough" decisions in the least amount of time, move on to the next problem, and free our conscious brains to focus on other tasks. Also, to act as a memory bank, to remember details and methodologies that can be recalled for later used. The role of the conscious is to act as a "governor", to teach and support the subconscious, to decide which problems need more deliberate attention, and to use tools like objective reason and logic to make decisions.

These two components work as a team, but still maintain independence. It is fascinating to think that while our conscious can influence our subconscious by learning and teaching it to perform sophisticated tasks like addition, reading, and driving, sometimes we cannot recall the name of a person we've met, no matter how much our conscious has tried to direct our subconscious to remember it.

The Subconscious

The subconscious is the "behind-the-scenes" workhorse of the relationship, handling numerous tasks quickly, efficiently and automatically. The subconscious is optimized for loop 1 and loop 2 thinking. It is focused on self and those close to us. If we are hungry, or our children are hungry, our subconscious is focused on feeding them, it isn't concerned with the plight of others far away. Our subconscious is especially adept at simplifying complex concepts and finding patterns. Although we often think of reason as a conscious activity, our subconscious can automatically deduce and infer from limited information. An amazing example of this can be seen here:

The Conscious

The conscious part of our cognitive system is what we often think of when we use the word "thinking." It is a slow, deliberative process that can use complex techniques such as logic and reason. It is the part of our brains capable of loop 4 and most loop 3 thinking.

Analogies

A good analogy is

Why is this important?

We can easily function without even recognizing the conscious and subconscious as having two distinct functions. We are capable of solving sophisticated problems. But, if we are to step back, and better understand human behavior and why people make the decisions they do, we need to better understand the way human brains work. Understanding the xxx is an essential foundational step in fourth loop thinking. When we are puzzled with why others react as they do, whether that may be supporting political candidates or making decisions on whether to get vaccinated, understanding human thinking systems can help find the answers.

Decision-making is a key role of the brain. Faced with choices and uncertainty, our brains must make quick decisions. Speed of decision-making, such as in fight or flight decisions, are more important than accuracy. Evolution has equipped us with many tools to help us make efficient decisions. Decisions that may be imperfect, and even incorrect, just need to be "good-enough" for the situation at hand. For example, unnecessarily avoiding a non-poisonous snake may be incorrect, but is usually good-enough for survival. And for a farmer in the 1600s, incorrectly believing that the Earth is flat, was good-enough for plowing fields and feeding one's family.

The ability to make quick, efficient decisions has become even more important with the advances in human civilization and technology. It is estimated that a modern-day human must make xxx,000 decisions each day! There simply isn't enough time to give each decision our full attention. Instead, our brains must quickly do a form of triage, prioritizing decisions, and determining which decisions deserve focused attention.

Evolution has dealt with this by giving humans two distinct "thinking systems" that work together as a team: the subconscious and the conscious. The goal of our subconscious is to quickly turn uncertainty into certainty. It doesn't ponder over all the subtleties and complexities, the goal is to make a fast decision and to move on to the next one. These decisions happen so seamlessly, so automatically, we don't even realize it is happening. Our subconsciouses are adept at finding patterns, filtering and prioritizing information, and even some impressively complex thinking. For example,

xxxx

The conscious part of our brain, what we typically mean when we talk about "thinking" is actually quite slow and has limited bandwidth compared to our subconscious brains. However, it excels at more complex reasoning than our subconscious.

And with practice, our conscious brains can train our subconscious brains to take over complicated activities, freeing our conscious to take on new tasks. Through training and repetition, we can make complex conscious tasks become automatic. Examples of this are reading, driving a car, catching a ball. Although our subconscious and conscious brains "talk" to each other constantly and work as a team, they can also be stubbornly independent. For example, we can consciously try to memorize a person's name or a date, but we can't be sure that the subconscious will cooperate.

Our conscious brains serve as a "governor" of the subconscious. They can either confirm and support subconscious instincts and beliefs, or they can challenge them. This process of challenging and "correcting" the subconscious is how we learn. A good example would be the way we see the earth. When we look at a farm, or at the ocean, our first instincts tell us that the Earth is flat. It sure looks that way. But our conscious brains can take in other information and use other sources to help us understand that the Earth is not flat.

The Importance of "Good Enough"

It is important to recognize that time is precious, and our there is significantly more information in the world than our brains can handle. The goal of our subconscious is to prioritize and make quick decisions that are "good enough" for the situation. Confronted with a bear on a path, it is faster and more efficient to avoid it than to correctly identify whether it is dangerous. A fast incorrect decision may be better than a slower correct decision. This is a hugely important and often overlooked fact of human evolution. It is hard to accept, it offends our belief in the value of truth.

What constitutes "good enough" will depend on the person, the perspective, and situation. What one person deems good enough will not be good enough for another. E.g. one student may be satisfied with a grade of B in a class, another will not. What is good enough for one situation will not be good enough for another. E.g. believing in a flat earth may be good enough for a farmer plowing their fields, but not if they are flying an airplane overseas. What is good enough from one perspective or thinking loop, may not be good enough for another. E.g. from Loop 1, thinking about oneself, a hungry person eating the last piece of bread is OK, but not so OK from loop 2 if one has a hungry child.

Evolution has equipped our brains with an amazing ability to quickly simplify complex problems, decide on a single definitive solution, and move on to the next problem. As with all "shortcuts", that means that sometimes we will make the wrong choice. Evolution favors those who can make more decisions quickly (even though some are less than optimal) over those who are slower but more accurate.

While schooling tends to focus on absolute truths, rules that are true in all situations and perspectives, the solution to most real-world problems depends on personal preferences and perspectives. The job of our subconscious brains is to simplify problems into a single definitive solution and move on to the next problem, not to consider other situations and perspectives. The world we live in is filled with uncertainty, but our subconscious brains are wired to create certainty.

The Role of our Conscious Brains

Many species have abilities similar to our subconscious brains, but few have anything like our conscious ability for complex reasoning, and the ability to override our subconscious decisions. Our conscious brains are what really distinguish

Only the conscious brain can do so. But conscious brain power is a precious resource. While our subconscious can make thousands of decisions a day, many simultaneously, our conscious brains are slower, can only focus on one thing at a time, and can more easily get tired. Given that, it is not surprising that evolution equips tries to preserve our conscious brain resources. In general, our conscious brains trust our subconscios

It is fascinating to consider that for most humans for most of history, believing that the Earth is flat is "good enough" for most day-to-day tasks. A farmer plowing a field can think of the Earth as flat and farm equally as well as one with a more holistic view. And, ironically, in some instances, it might actually be safer to have an incomplete view of the facts. In the 1300s a fisherman who believed in a flat earth might be more likely to stay closer to shore for fear of falling off the edge. And given the technology of boats and weather prediction at the time, might actually have a better chance of survival than a fisherman who strayed too far offshore.

A Loopy Analogy: Hamlet at the Globe

A good analogy for thinking loops is to think of a play. For illustration, we'll choose Hamlet pondering Yorick

In Loop 1, we are Hamlet. We see the scene from Hamlet's eyes. His focus is on the other actors on stage and our lines. When Hamlet is offstage, he does not know what action is taking place on stage. [Caption: Loop 1 Be in the moment]

In Loop 2, we are an audience member sitting in the center of the first row. Our focus is all the actors, including Hamlet. We know what happens both when Hamlet is in the scene and when he is off stage. We see a "cropped" version of the stage, much of it is outside our primary line of vision. [Loop 2: The play's the thing]

In Loop 3, we are sitting in the balcony. We see the whole stage, we see the whole theater. We notice the full set, we see the lights. And very importantly we see the audience. We know if the theater is empty or full, we know if people are yawning or engaged. How others react to the play affects our own perceptions. If they are laughing, we are more open to laugh ourselves, etc. Our views may be influenced by a review we had read before seeing the play.

Humans are optimized for third loop thinking. We can very successfully solve problems. We can spend our entire lives in the third loop quite successfully. The third loop is an essential component of critical thinking. There are many areas of study, such as logic, analysis, and complex mathematical calculations that help us become better third loop thinkers.

The Courtroom Analogy

Our brains are constantly faced with conflicting viewpoints, and have to reach a decision, much the way a judge does. We like to think that we are objective, and while our brains are capable of doing so, there are also inherent biases. Very similar to what happens in a courtroom. Our conscious brains not only play the role of the judge but also the prosecution and the defense. In this case, the defendant is our own subconscious. Imagine a judge who is trying a case against a member of his/her family... they can try to be objective, but of course will favor the defense.

And while our conscious brains can act like an objective judge, capable of taking into account outside information and evidence, they can also act like courtroom lawyers whose client is the subcioncious. They can become advocates to support the subconscious. Finding a line of reasoning to defend the conclusions of the subconscious, and casting doubt on alternative viewpoints. Imagine a courtroom where the defense attorney is also the judge. That is essentially the situation with our brains.

For me, this has been an invaluable perspective to understanding human behavior and how some people reach seemingly illogical conclusions. When our subconscious beliefs "get it wrong," it takes deliberate conscious effort to correct it. And our conscious thought is limited, we can't always correct what our subconscious believes, we simply do not have the bandwidth to do so. Each of us has to prioritize and decide independently. And we don't all share the same priorities. Farmers trying to bring in a crop are more likely to prioritize expending their limited conscious energy into finding ways to feed their families, than to contemplate the shape of the plant Earth. And thus less likely to challenge imperfect subconscious beliefs. Even incorrect beliefs can be good enough for many situations.

An example of this in action would be the progression

Our conscious brains think they are in control, but they can't actually tell the subconscious what to do.

The conscious and subconscious parts of our brain have somewhat different goals. Our subconscious favors speed and efficiency. It makes quick decisions based on the information at hand. The goal is to get a seemingly good enough answer to move on to the next. Efficiency and speed are more important than making the best, or most accurate decision. Our subconscious is very adept at simplifying complex problems, using patterns, and converting uncertainty into certainty (e.g. deciding to fight or flee). The value of a pattern is that if information is missing, we can make an educated guess on what is missing, fill-in and reconstruct. Of course that also means that occasionally we get it wrong. There may be better choices for what is missing but we don't have the time to find out. It picks one and moves on.

These subconscious traits have been honed through generations of evolution. We share many traits with other animals. It is our conscious brains that truly differentiate us from other species. While our subconscious brains settle for good enough, our conscious brains do not settle for good enough, they aspire to better than that. Still, time and energy are not unlimited, there are only so many hours in a day and in a life, so our conscious brains still ha

ur conscious brains can engage in complex thinking, and

And there is a natural defensiveness. Once we believe that something is true, and we build other beliefs upon that, our first reaction is to fight that off. This makes sense. If we had to constantly question what we already know, we'd have no time to learn new things.

Subconscious Loops

By the time we reach adulthood, most of first loop and second loop thinking happens entirely subconsciously. And a good deal of third loop thinking as well. We typically think of reason as a conscious activity, but our subconsciouses are quite adept at complex reasoning. Example here:

And you can even do that while chewing gum and standing on one leg, tasks that also require conscious thought.

The role of our conscious brains is to continue to learn new things, to refine what we already know, and to take on problems that are too complex for our subconscious to handle. Faced with an xxx, our subconscious wil steer the wheel xx, but then pass it on to our conscious to deal with more xxx.

However, our conscious time is limited, and our subconciouses are aware of this, so act as a gatekeeper and are quite influential in letting things get to our conscious brains.

Although we tend to think of reason as a conscious activity, by adulthood, our subconscious brains are capable of sophisticated reasoning. xample here:

In adulthood, while our conscious brains evolve to handle more complex reasoning, they still are not able to multitask. To prove it, try solving these 2 math problems at the same time:

And there are only so many hours in the day. Our conscious brains need rest. Our heads "hurt" when we have to focus on a complex task for too long.

A Perspective on Human Thinking from the Fourth Loop: The Importance of Efficiency

Subconscious vs Conscious/

Sub makes quick decisions based on the information at hand. The goal is to get a seemingly good enough answer to move on to the next. Efficiency, and the ability to make quick decisions is more important than making the best, or most accurate decision. Our subcionscious' can ask our conscious for help when information is missing, but first it tries to fill in the missing information. Our subconscious does not think in facts but rather in patterns. The value of a pattern is that if information is missing, we can make an educated guess on what is missing, fill-in and reconstruct. Of course that also means that occasionally we get it wrong. There may be better choices for what is missing but we don't have the time to find out. We pick one and move on.

Our subconscious are incredibly fast.

We typically measure the quality of thought in terms of its use of logic, rationality and accuracy. We take it for granted. This makes sense from an objective, third loop perspective. But when we step back to the fourth loop, we suspend assumptions, consider different perspectives, other variables. And from that perspective, we see that evolution is the driver of human thought. Logic helps us survive, so therefore evolution favors logic. But there are other drivers as well.

One of the most important evolutionary drivers of human development is time. Time is a precious resource. Rigorous thought takes time. The ability to make speedy decisions is often more important to survival than an absolutely correct one. Faced with a xx snake, mistaking it for a xxx.

Human cognitive systems are amazingly complex. Although we typically equate "thinking" with conscious thought, the reality is that most cognitive function happens subconsciously. Our subconsciouses have immense capacity. We can remember an amazing amount of information. We don't consciously decide to remember something, our subsconscious systems do most of the work. And our subconsciouses can be trained to perform complex tasks. But conscious thought is limited. Our conscious brains can only concentrate on one thing at a time. (Math prob) and for a limited amount of time each day.

So while truth and logic are important, our cognitive systems have to do a form of triage. Time must be allocated judiciously. Deciding when an answer is "good enough" for the task at hand. Efficiency is the ultimate judge. We don't always have time to find the best answer, what we have to do is to find a good enough answer in the least amount of time. Given this limited amount of time, for most everyday problems, it is better to make multiple "good enough" answers than one perfect answer. Xx's have estimated that in the modern world, the average human makes xx,000 decisions per day.

To me, this is an incredibly useful perspective when trying to understand others. Unlike in math class, for most real-world problems there is no universal definition of what constitutes "good enough." The criteria for "good enough" may vary by individual and situation, it can be especially frustrating.

On the other hand, the human race would not have evolved very far if we all settled for good enough. So much of our innovation and advancement of civilization is because some did not settle for "good enough." And this an interesting paradox of human thought. Even though our cognitive systems are biologically wired for efficient "good enough" thinking, our brains are also wired to make us not believe it. *I suspect most readers experienced that exact thing on reading the above. What was were your first reaction to reading that human thought favors "good enough?" If you are like me, your first reaction was to disagree, perhaps even vehemently. You may even have felt an angry reaction, increased adrenaline. The instinct was to fight and ask "what kind of a world would it be if we all settled for good enough?")

Efficiency of

Interestingly, the instinct to fight against the idea that we settle for "good enough" is an example of cognitive efficiency. "Good enough" is not a motivating concept. No sports coach would ever succeed telling her players to go out there and "do just good enough." Instead we use motivational phrases such as "give 110%." We know 110% is impossible, but it motivates us to do better.

There are several other examples of this cognitive paradox. One is as the Duning-Kruger effect. It has been shown that we all tend to overrate our knowledge and cognitive abilities. It has become popular for cogpsy's to see this negatively, but I see it as in important evolutionary advantage that helps create efficiency. We all know the value of confidence in performing task. DK gives us confidence.

But, of course, not always. Sometimes confidence gets us into trouble, we also all know the dangers of "overconfidence." And that is the reality of efficiency and settling for "good enough." It is far from perfect, and what we believe to be "good enough" doesn't turn out to be good enough. Sure, if we had more time, or prioritized conscious thought differently, we might have come to a better answer. But without the benefit of hindsight and unlimited time, our cognitive systems favored the most efficient choice. Efficient doesn't mean best.

Trust

The paradox o

And this gets us to something else that

makes us human. We live in societies. We pass knowledge on from one generation to another. We don't all have to be truth-seekers. As long as someone makes the effort to not settle for good enough, makes the effort to find more, that information can be passed onto others.

it makes sense that evolution favors efficiency, even though we sometimes make decisions that may seem irrational

Time is a most precious resource and cannot be separated from most decision-making. Faced with a predator, a quick decision may be the difference between life and death. Additionally, the human conscious brain is only capable of one complex thought at a time (as an example, try to do these two calculations sumulatenously) so

Conscious brainpower is a limited resource

The more we can do subconsiously, the more we can do, and also allow us to save conscious brain focus for other tasks.

Many factors enter into decision-making.

Trust

Trust is efficient. Instead of having to invest time to discover something for ourselves, we can quickly gain that knowledge by trusting another source. Parents, schools, encyclopedias are all examples of trusted sources.

There are biological advantages to trust. A child predisposed to trust their parents is more likely not to run into traffic to discover for themselves whether getting hit by a car is dangerous. And trusting a stranger who tells us to watch out for the slippery ice can help save a trip to the emergency room. And we tend to trust people we like. Trust also correlates with thinking loops. We trust ourselves most (loop 1). Next we trust those who are in our circles, those who are friends, and those we like.

Of course, trusting strangers can also be dangerous, and children learn to trust their parents warning to be wary of strangers. This is an example of a hierarchy of trust.

The ability to have levels of trust, and the reliance on information from sources is so important to human development, that our brains have special wiring to deal with information that comes from sources. Cognitive scientists call this source monitoring. Source monitoring has two components. In the first, we have subsconscious wiring to help us associate knowledge with the source it came from. The second associates a source with a level of trustworthiness. What is interesting about that, is that our subconscious only rates the source as a whole, not the specific bits of information from the source. So, if we trust our dentist to fill a cavity, our subconscious will also trust their views on restaurants. This is why celebrity endorsements are so effective. Our conscious brains can of course override this if we are willing to devote conscious time to thinking about it.

Efficiency takes time into account. In math class, when we are given homework, we can take as long as necessary to solve a problem. The same isn't true on a standardized test where we have to make calculated decisions on how much time to spend on a specific problem. For the purpose of this discussion, I will define mental efficiency as finding a "good enough" answer in the least amount of time. Of course, what is good enough will vary by individual and situation. What is good enough for one person, many not be good enough for another.

Although we often think that the role of our brains is to find the best answer, our brains are actually optimized to find a good enough answer in the least amount of time. I.e. to be efficient. One can think of our brains like a Swiss Army Knife. The blade on a Swiss Army Knife, the screwdriver, the corkscrew are not as good as a dedicated tool. When put to extreme tests they might even fail. But for most purposes they do the job, and they are lightweight and take up very little space. And when space is important, such as when hiking, the benefits of weight and space far outweigh the negatives of less robust tools.

Prioritization

Efficiency requires prioritization. Given multiple choices and limited time, we don't have the luxury of exploring each option and choosing the best. Instead we make a choice based on prioritization. And human evolution has helped define our priorities.

Thinking loops 1 and 2 are examples of prioritization. In order to

Sources

Discovering through experience is the best way to understand something, but it is inefficient. It is much more efficient to let others do the work, and to gain from their experience. Our human brains are optimized to gain knowledge from sources. The majority of our knowledge comes from teachers and books, not from our own individual discovery. The ablity to learn from others, to pass complex knowledge from generation to generation, sets humans apart from most other species.

We are wired to believe others.

Patterns and Reconstruction

We can learn a lot of individual facts, but it is more efficient to remember a few facts, and reconstruct knowldege on the fly. We don't "know" that one more than 2543 is 2544. But we know a rule for incrementing a number and we can apply that rule to any number, no matter how many digits. Talk about efficient!!

Our brains are optimized not to remember individual pieces of data, but rather to recognize patterns. Patterns allow us to fill in things we have forgotten, and to construct knowledge on the fly, much of it subconsciously.

Gears

The Role of Fairness

However, an interesting human trait is to deny this....we like to believe that we have higher ideals, to believe that we know more than we do. That seems odd, but it makes evolutionary sense when one steps back to the fourth loop.

Third loop thinking emphasizes rational thinking processes, such as logic and reason. Humans are capable of very sophisticated thinking. And thus, it is difficult to understand why others reach what seem to be irrational conclusions that are not justified by logic. One popular field of critical thinking has gone so far as to categorize such thinking as "cognitive biases." xxxx lists over xxx cognitive human biases. And the thinking goes that if we can be educated and made aware of these biases, we will become more rational thinkers.

But when I step back, I wonder why these "biases" exist? If they are so bad, why wouldn't evolution have snuffed them out long ago? Perhaps our

There are many resources to help hone our third loop thinking. Our educational systems, and most books on critical thinking focus heavily on this third loop. Third loop skills are an extremely important in critical thinking, but the focus of this site will be on fourth loop thinking.

From the third loop, we observe that people often seem to

. It is hard to understand why the evidence that seems clear to us, often seems to be ignored by others. Taking a step back into the fourth loop allows us to take a closer look at our assumptions.

The following are some foundational concepts from the fourth loop:

The human brain, thinking processes, and the role of time

Our brains were shaped by millions of years of evolution. Our biology, including our thinking processes won out over other humanoid species. Even those processes that may seem imperfect likely exist for a reason.

Efficiency, Effectiveness, Expediency (Good Enough)

All of these terms describe the concept of good enough in the least amount of time. I included expediency here for a reason. The dictionary decscribes expediency as ",,,, sometimes immoral," Depending on the criteria for what constitutes "good enough", sometimes the immoral answer provides the fastest answer.

Filtering and Prioritization

Sources

Proximity / Thinking Loops

Fairness

Pattern Thinking and Relationships

We tend to think of knowledge as a series of facts with a good index, similar to an encyclopedia with a search engine. But a more efficient way to think is through patterns and relationships, which is just what our brains are wired to do.

One of the most interesting aspect of patterns is that they can look very different based on where one starts in the pattern. And patterns can be overlaid for new uses. Evolution wired us to reduce, reuse, recycle, long before the slogan came about. It wasn't for idealistic environmental reasons, it is simply more efficient. If one has limited storage space, then it makes sense that a tool that can be used for multiple things will be more valuable than a specialized tool. Likewise a tool that takes up less space will be more valuable than a larger tool, even though the larger tool may do a slightly better job. As long as the tool we choose is good enough for most situations.

The most efficient patterns are those that repeat. For example, here is a numeric pattern 2,2,2,2,2,2,2.... that we can simply remember as "always 2".

That may seem simplistic, but it is

Here are a few efficiencies of patterns:

reconstruct

The same pattern can look quite differerent depending on our starting point and grouping. Let's take a list of even numbers for example:

0,2,4,6,8,10,12,14.

Most people will quickly deduce the pattern and can easily predict what number(s) will come next. Or if a number is missing, we can easily deduce what it was.

Interestingly, this patter is based on another pattern. In this case it is 2,2,2,2,2,2,2. Which we can shortcut in our minds as just 2.

But humans think in terms of patterns and relationships. And again, the reason

Humans are what sociilogists call "pro-social." We act individually but are much more efficient in social groups. Societies do not work well if everyone acts immorally. So the concept of "fairness" is deeply rooted in our evolution. Perceptions of unfairness trigger anger. Anger is an emotion that forces us to focus more on self preservation. It is important to recognize that it is perceptions of unfairness that matter, and those perceptions are based on the efficiency mechanisms described above.

Dealing with Uncertainty

The remainder of this site is organized into the following sections.

- Fourth Loop Thinking: Understanding Human Thought Processes

- This section discusses how our species has evolved to give us innate abilities, which affect the way we approach problems. As humans, we are all subject to these innate biological realities. And one of those abilities, is the ability to override any innate xxx with effort and conscious thought. But time is limited and precious, we can't do it always in all situations. TIme is a hugely important input in human thinking.

- Techniques for Critical Thinking from the Fourth Loop

- This section discusses some techniques to help us use that understanding of human thought processes, and models and techniques that can aid in critical thinking.

- Uncertainty: A Fourth Loop Perspective

- Certainty is much easier to deal with than uncertainty. Humans like certainty. We live in an uncertain world. So, humans have developed many techniques and approaches to map uncertainty to certainty. Looking at uncertainty anew from the fourth loop can provide some valuable insights and approaches to uncertainty.

- Analysis of Current events and Contemporary Problems : From a Fourth Loop Perspective

- This section will take a fourth loop approach to look at many of today's complex problems.

While readers should feel free to skip around this site, first time readers would benefit from at least skimming in order.

For More Information

Page 2: Fourth Loop Foundations: Humans are Human (Understanding Human Thought Processes)

One of the most difficult aspects of fourth loop thinking is to simply acknowledge that we are all human. This may sound simple, but as humans we tend to overestimate our abilities and knowledge, and we tend to believe what we want to believe is true. We have an idealized view of reality, we jump to conclusions based on little evidence, sometimes contrary to evidence. And a natural trait of humans is to deny that all share those traits.

When we look at that from the third loop, we see these as flaws. These "flaws" are commonly called "cognitive biases" and there is lots of literature/effort spent on identifying them. xxxx lists over xxx identifiable cognitive biases. Much of current critical thinking books and literature focuses on these biases.

But fourth loop critical thinking takes a more pragmatic approach. If these traits are so bad, why have homo-sapiens (our species that we call "human") thrived and other humanoid lifeforms have gone extinct? If these traits are so bad, wouldn't evolution have weeded them out over time. Perhaps we should recognized that these traits help optimize our survival as a species? Maybe we should accept them the way we accept that our knees only bend one way. Yes, they make some things more difficult, but overall the benefits outweigh the negatives.

With practice and exercise, gymnasts can overcome many of these restrictions, and so too can thinkers overcome some of our mental restrictions through education and practice. But, doing so takes time and dedication, and there are limits. No matter how hard a gymnast trains, their knees still only bend one way.

But there is good reason for that, otherwise it wouldn't have survived over 100,000 years of evolution. It serves us well because it saves time, and time is a precious resource, in human thinking processes. Making the best choices takes time. With limited time, it is much more important to make multiple "good-enough" choices (with a few "incorrect" ones mixed in) that to get it right. That flies against our beliefs in the value of truth and evidence, and the foundations of our education system. E.g. we would not be very happy with a school that passed a math for adding 16 and 32 and getting 47, even though that answer would be good enough for many real-world problems. Our unhappiness with that would be for good reason. And thus the paradox: there is good reason to believe in the importance of getting it right, but also good reason why humans aren't built for getting everything "right."

This can all be lumped under the simple concept of "Efficiency." Given unlimited time, we can afford to get things right. However, with limited time, and limitless problems, the optimum solution for human survival is for them to get "good enough" answers to as many problems as possible. And of course, "good enough" is subjective, it depends on the context and situation, and determining whether something is actually good enough requires time and is this inefficient.

When humans jump to conclusions, we are making efficiency choices. We get what we believe are "good enough" answers, and by definition, that also means we'll sometimes get it wrong. Odd as it sounds, the human race has survived not because we get things right, but because we often get things wrong... but we get enough things "right enough."

Efficiency and Expediency

Paradoxically, fourth loop thinking isn't efficient. It is a luxury that only exists when we have enough time, when we prioritize it over other endeavors. It is not something we can do all the time, nor we can expect everyone to do it. And a key fourth loop concept is understanding that, and recognizing that it is human to value "good-enough" over "best-answer." This is far from morally ideal, it leads to great societal inequities, but it is human.

Human priorities of what is "good-enough" map to the 3 thinking loops. "Is it good-enough for me," "is it good enough for those close to me," "is it good enough for what I see in front of me?"

Science

Science gives us confidence to backup our conjectures and beliefs. And the value of humility in sometimes finding out we are wrong. And thus the lesson of objectivity.

Science is important for finding truth, but perhaps even more important is the value of learning we sometimes believe things that aren't true. It isn't a flaw to be wrong, but we can improve.

----

So, our human natural tendencies help us simplify complex problems and jump to quick answers. This is good enough for everyday work. But for more complex problems, fourth loop thinking help us find more accurate answers. So how do we overcome our natural tendencies? The answer is to develop methodologies before the fact. Science is essentially a methodology.

Which is frustrating because good-enough for one class of people can lead to inequities for others. Northern whites may have disagreed with slavery, but the economic system that included slavery was "good-enough" to allow them to

it can lead to societal inequities.

Theory of MInd

ne of the most amazing and beautiful traits of humans is "theory of mind." We move from a purely self-centered point of view (how does this affect me?) to be able to see things from another's perspective (what would I do if I were them?). This is a form of stepping back. And of course as we grow older, we gain a more sophisticated and nuanced theory of mind.

An example of this can be seen in the way "never again" is interepreted. As someone who grew up Jewish, with the holocaust of Nazi Germany still in the memories of my parents generation, "Never Again" is rooted in my soul. Although I am not religiously Jewish, my identity, and that of so many other Jewish Americans, and Jews around the world, the central binding tenet is the long history of anti-semitism.

For some, the focus is on anti-semitism. To wipe out the long history of anti-semitism. And for some of us, that extended to other groups that have been subject to anti-ism. Racism. And thus the long-time affinity between many American Jews and the civil rights movement. There are many groups focused on never again. Some, like the ADL, step back and focus on all forms of discrimination and xxx.

Living in Lowell, among many Cambodian refugees, escapees from the genocide of the killing fields,

Little Canada, holocaust, never again

---

Face facts

Easy to say, much harder to do when the facts don't align with what one wants to believe, when it challenges our foundations. Only if we have a strong foundation, based on many pillars, can we take away a pillar. In such cases, it actually strengthens our foundation. But when the pillars are weak, or singly based, it is difficult. Think of a stool: take away one leg, and the stool falls, no matter how strong the legs. A chair can lose a leg and still stand, a bit wobbly. A five or 6 legged table can function strongly.

The current Presidential race is a good illustration of the interaction between thinking loops, the role of momentum, and the difficulty of stepping back.

In the current race, the presumptive nominees are Donald Trump and Joe Biden. The primary process has been followed, each has clearly won the process. Each side feels that the xx of their candidate fits their views.

And yet if you step back it is hard to imagine that of all the possible candidates, these are the best 2. I'm not talking political viewpoints, just looking at them in terms of how they communicate. While implementation is important, the ability to communicate, to represent our country, is also an important part of the job. And one doesn't have to drill very deep to see it.

Simply put:

Donald Trump exhibits behavior that we would not tolerate from our children. The name-calling, the blaming others, the self-focus.

Joe Biden sounds old. No one gets younger. This isn't age-ist, this isn't about age, it is about how one acts, how one is perceived by others. If one were interviewing candidates to be a baby-sitter for one's children, to manage a household budget, would either of them get picked?

So, we now are electing the President of the United States, the leader of the free world, and these are the candidates?

But so often momentum and process get us caught. We are so far down a road that we see no way to get back, even if our fourth loop viewpoint tells us how un-ideal it is.

JUst step back for a minute, think of the United States of America and its long history. Think not just of your own political views. Instead of having to decide between Donald Trump and Joe Biden as candidates, what if the choice was between two sets of options:

Election between Donald Trump and Joe Biden

or

Election between Nikki Hailey and Gretchen Whitmer

Which slate best represents the United States of America? Sometimes in problem solving the solution is not the hard part, the difficulty is finding a new path.

Writing is good for thoughts, but how do we express feelings?

Music, art? Maybe an incite into Rothko?

Concept of Proprioception: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proprioception

I can't stress enough, the importance of thinking about efficiency of thought

accepting this as a useful feature of human thinking,

We can sometimes see it in others, but are less likely to acknowledge in ourselves. And when we do see it, we treat as a flaw to be corrected, instead of recognizing that it is simply a fact of being human

Especially for those of us with an "academic mindset," we like to believe that we are evidence-based.

A good example of this is our approach to truth and "correct" answers. We tend to minimize the hugely important role that time plays in human thinking. And we tend to think of those who don't take the time to "get it right" as flawed or lazy.

Fourth loop requires us to suspend judgment and to adopt what is often called a "learning mindset." Instead of thinking as others as unreasonable, we try to understand how a reasonable person could come to that perspective. Instead of seeing human behavior as being flawed, we simply accept it as being human. Just as we don't think we are flawed because our knees only bend one way. Instead, we accept its evolutionary importance, and simply take it into account as a fact. We turn the golden rule sideways: Instead of treating others as we would like them to treat us, we try to treat others as THEY would like to be treated. Instead of thinking of what we would do in other's shoes, we focus on what THEY would do, we try to understand them.

An Everyday Example of the Fourth Loop Approach to Thinking

Before I go on, I want to make it clear that this loopy model is not something that exists in literature (e.g you can't just google it and find other descriptions.) It is simply a model that I find useful, an amalgam of other models that have helped me hone my thinking. [Link to the amalagam]

Everybody is more than capable of fourth loop thinking, but it doesn't tend to occur naturally. It requires a bit more conscious effort to take the step back, outside of our forward vision. But it can reveal wonderful unseen perspectives, even for everyday problems,

Here's an rather mundane example of how the fourth-loop has helped me

so I want to try to give another example that will hopefully help clarify the concepts. So I wanted to present this example from everyday life.

McDonald's is a xxx billion dollar company. xxxx. But its success is hard to comprehend from the first 3 loops. The food is not very nutritious or healthy. Their hamburgers would never win any taste tests. And there is nothing about their food that a competitor couldn't duplicate. From a business perspective, based on everything I learned in businesss school, if Ray Kroc had offered me a chance to invest in McDonald's at the beginning, all my reason and business training would have me decline and tell him all the reasons it wouldn't work. And I can cite countless examples of other businesses who went out of business with more competitive edge than that.

Yet obviously McDonald's was a great success. From the third loop, we tend to stick to our guns and find other explanations that don't challenge our core beliefs. Since all of the above reasoning was sound, a common conclusion is that people are just susceptible to marketing, or perhaps we think of them as stupid or uneducated. Or perhaps addicted to sugary drinks.

But can really be the only reason that McDonald's is a multi-billion dollar company? From the fourth loop we may recognize that McDonald's is a bout meeting people where they are, not where we think they should be. And that can give us great insights that can be useful for

and I would have been completely wrong. The reason is because I was focused on the 3rd loop. My logic wasn't flawed. But I didn't step back to the fourth loop. From the third loop I might try to justify my reasoning and say that it shows that people are stupid and/or susceptible to marketing. But from the fourth loop, we understand that McDonald's business is not about high-quality food or nutrition, it is about convenience and meeting people in their world, not an idealized world of what people should do. It meets a need, is consistent and reliable. And the evidence is in the fact that xx. It is incredibly efficient for consumers. It provides a "good enough" solution in very little time, and requires very little conscious effort. It can be counted on to provide exactly what one expects. It seldom exceeds expectations, but it almost always meets them.

One could call that consistent mediocrity. Which that would be technically accurate, but pragmatically inaccurate. Why? Because in practice, "mediocrity" is perceived as negative. Given a choice of restaurants, few would choose a restaurant described as mediocre. And yet in practice, consistency may be more important than xx. If there was a restaurant that served incredible food 8 out of 10 times, but 2 out of ten served really lousy food with lousy service, few would go back. That is another important aspect of fourth loop thinking: not only relying on "dictionary definitions" of words, but recognizing that human language, words have many definitions, mean/imply different things to different people in different contexts. The differences are often subtle, but can significantly affect perceptions.

The Importance of the Third Loop Should not be Minimized

Most everyday human thinking takes place in those three loops. Loop 1 is self-care, loop 2 is represented by the golden rule: . "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." Analysis and rigorous investigation, an essential aspect of critical thinking, takes place in the third loop. Logic and the scientific method , and many great inventions have come from third loop thinking. Those 3 loops serve us well, and problems can be solved with 3-loop thinking. It is incredibly efficient.

The importance of the third loop should not be minimized. However, sometimes 3-loop thinking leaves us stumped, and without stepping back, we make little progress. Our solutions seem logical, so when they don't yield the results we expect, we tend to double down, to think the problem is with our implementation. So, for example, when tougher drug laws don't stop the flow of illegal drugs, a natural reaction is to double down and make the drug laws even tougher. And we certainly see that opinion played out in the political arena today. There are many examples of this third-loop impasse, and some extreme mental gymnastics to defend our original solutions. In some cases, this may lead to conspiracy theories. If we believe that our initial conclusions are correct, and they don't yield the desired results, then it can feel "logical" to concoct other explanations.

Aside/Tidbit: Amalgam (Rename - put in own page)

For those interested, this outlines my evolution to settling on the four loop model. I think it is rather illustrative of how ideas come to be. While there may ultimately be a light-bulb moment, the evolution is much longer, and the spark comes from many other bright ideas.

The first spark toward the fourth loop came from a class in Negotiations in Business School back in 19xx. We read "Getting to Yes" written by several professors at the Harvard School of Negotiation. The takeaway that has stuck with me ever since, and served me well in a myriad of situations, was the concept of "going to the balcony." That so often in negotiations the sides are so focused on winning that the big picture gets lost. From the balcony the goal is objective analysis and the search for a win-win situation. Neither side may get everything they want, but both get something more than they would have without negotiation.

Moving on, Pielke, stakeholders,

Triple loop thinking. Fuller three.

Tried to force my thoughts into the model. Even my "thesis" put everything into the 3 loops.

My epihany came when I stopped being constrained by 3, and realized that 4 made more sense for my model. Once I did that, things seemed to fit. Readers may reasonably ask about loops beyond 4. No doubt there absolutely are, one can always step further back. But I also realized that trying to categorize them is beyond my capabilities. I'm having enough trouble getting a handle on the fourth loop. I will leave the 5th loops and beyond to others. I have no doubt that great thinkers like Stephen Hawking were able to think in loops 5 and beyond.

I think this process is typical of the way new ideas form. We combine knowledge from other ideas, play around with them, add a bit from here and there, and put them together in a new way. Ideas don't happen in a vacuum. I bristle when I hear people describe themselves as "self-made" or xxx. One of the most important abilities of humans is our ability to pass knowledge from one to another, from generation to generation, and to use reason to put them together in unique ways. To think one does this on one's own is a good example of Loop 1 thinking. When one steps back, one realizes all of the institutional, educational and societal influences that enabled them to "make themselves."

The Critical Fourth Loop

Problems like these can look different when we take another step back into the fourth loop, when we take a break from solution-finding, and focus on problem-understanding. This fourth loop is more difficult, requires significantly more time and effort to step back. It can be quite nebulous and overwhelming. It seldom yields definitive solutions and often uncovers more questions than answers. And it is easy to avoid simply by keeping our forward focus. Stepping back takes significant cognitive effort and a willingness to reexamine our own beliefs.

Nevertheless, the fourth loop is essential to critical thinking. Innovation and "out-of-the-box" thinking happen in the fourth loop. Using the theater analogy, in the fourth loop we take a big step back from the balcony. We leave the theater entirely and see it from the outside. We see all those people that are not in the theater at all. Some who might love to see the play, some who don't give a whit about poor Yorick, and some who don't even know the play is going on. All are focused on their own thinking loops, they have things that are higher priority to them than being in the theater at that moment.

This fourth loop requires us to suspend judgment. Instead of thinking of what we would do in other's shoes, we focus on what THEY would do, we try to understand them. Instead of thinking of them as flawed or unreasonable, we try to understand how a reasonable person could come to that perspective. Instead of seeing human behavior as being flawed, we simply accept it as being human. Just as we don't think we are flawed because our knees only bend one way. Instead we accept it, understand the evolutionary importance, and simply take it into account as fact as we look to new solutions. We turn the golden rule sideways. Instead of treating others as we would like them to treat us, we treat others as THEY would like to be treated.

This site will focus on the fourth loop. It will focus on 3 main areas: foundational work toward a better understanding of human thinking processes, techniques to help us be better fourth loop thinkers, and analysis of current problems from the fourth loop.

A

We look at probabilities such as vaccine efficacy in a different light, we see averages and statistical distributions in a different light. We recognize that sometimes the best choice will yield a negative result, and sometimes the worst choice will yield a positive result. And that a reasonable human being who happens to witness that, will naturally question the validity of recommendations. And we recognize that our reliance on sources will skew our perception of the data. This is no panacea, the fourth loop doesn't provide us an answer to gambling addiction or vaccine denial, but it does allow us to hone our solutions to recognize those realities. That is the essence of more holistic, more pragmatic, more objective, critical thinking.

The focus of this website will be on the fourth loop, trying to better understand how others think, how we think, and techniques we can use to be more objective critical thinkers.

Here are a few real-world examples:

Mathematicians and statisticians can tell us why gambling is a losing proposition. We can calculate the odds and expected values and know that the only winners are the casinos and those running the game. Yet gambling is a $xb industry. Based on this, we conclude that a reasonable solution is for more education on the subject, more "critical thinking" skills. Yet even highly educated people gamble. Statisticians gamble. We know how bad cigarettes are for your health. Yet many doctors and nurses, clearly educated on the dangers, still smoke.

Another example came from the Covid vaccine. Our scientific community did so much to quickly develop an effective vaccine against a pandemic that was claiming so many innocent lives, and affecting our way of life. For many of us this seemed like THE solution. I can remember the sheer joy of myself and so many in line for that first vaccination. A true miracle and testament to human progress. We assumed that others would think the same way and everyone would get vaccinated. Certainly that would be the case in education-oriented Massachusetts. Yet xx% of the population never got vaccinated, xx% right here in Massachusetts, and the pushback against it still seems mind-boggling.

This is a wonderful example of forward thinking. More education seems a logical solution. However, the real-world data does not jive with what we expect. And faced with that reality, we jump to new solutions that ultimately are just doubling down on previous solutions. This is a very common human behavior, and historically has led to more extremes, and further polarization, creating an "us" vs "them" mentality.

One of the most difficult aspects of probability is that sometime the best behavior will yield the worst result,

We begin to understand that gambling is a form of entertainment and escape, it allows people a wonderful opportunity to dream of what they would do in a different financial situation.

If education is the answer, and we aren't getting the desired result, then more education is what is needed. We start taking sides, devolving into an "us vs. them." e.g. "They need to be more educated." And at the same time, "they" are thinking the same about "us." At the same time, a Pugh poll shows that confidence in our educational institutions is waning.

This isn't meant to say that education isn't important, or to diminish its importance in any way. Education is essential for long term solutions. My point is simply that in the short run, it isn't enough. We need to step back from our jump to solutions, and re-evaluate.

instead of stepping back and focusing on a new understanding of the problem, we double down and

From the 3 loops, the solution to both these issues seems clear: We put ourselves in their shoes and think of what would make us change our minds. So we double-down on those techniques. More education, more detailed explanations from the medical community, more briefings by Doctor Fauci. And although we don't say it out loud, our internal tendencies, our loop 3 conclusions are to throw up our hands and think of them as unreasonable people. We begin to see them as the enemies.

Things look a little different from the fourth loop. We see that even Mathematicians gamble, even some medical professionals became vaccine deniers. Instead of starting with "why can't they think more like me,"

We start to question why from a more objective, less judgmental point of view. Instead of starting

If humans, and human brains have made it through 150,000 years of evolution,

But when we step back, and we see that gambling is a $xB industry, we take that empirical data into account and question whether our approaches are effective.

Instead of thinking of people who gamble as stupid and uneducated, we take a look at our human evolution and makeup, and look for reasons why this behavior exists.

more nebulous and harder to grasp, and easy to avoid by keeping our heads forward.

But that is incomplete. True critical thinking requires another step back into a fourth loop.

The fourth loop takes another step back. We take into account not only what we see, but what isn't in our sight of vision. In the theater analogy, this means looking from outside the theater. We see the people not in the theater at all. Some too busy with other priorities to even notice the theater, others who might like to be there but aren't there.

Other Perspectives

Loop 2 is the beginning of being able to see other perspectives. It is essentially the golden rule And there is an example of the loop 1, self orientation. Because we are looking at what WE would do in their shoes, not what they would do. The golden rule doesn't say "as they would like to be done to." This is a crucial aspect of human behavior. Despite our advanced thinking in loop 3, we are still looking at it from a personal perspective.

And one can see that happen over and over in political debate. In so many cases, the thinking is that "everything would be okay if THOSE people would just think like I do." And that applies to those on both the left and the right, moderates too. Analytical scientists, cognitive psychologists, and conspiracy theorists.

The Critical Fourth Loop...and Beyond